What is causing Type-2 diabetes in Canadian Aboriginal people?

- Sabrina P.

- Mar 12, 2018

- 10 min read

Updated: Mar 28, 2018

The indigenous people of Canada are referred to as Aboriginal people who, under the Canadian Constitution Act (1982), include three distinct groups: First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people of Canada (Cameron, Plazas, Salas, Bearskin & Hungler, 2014).

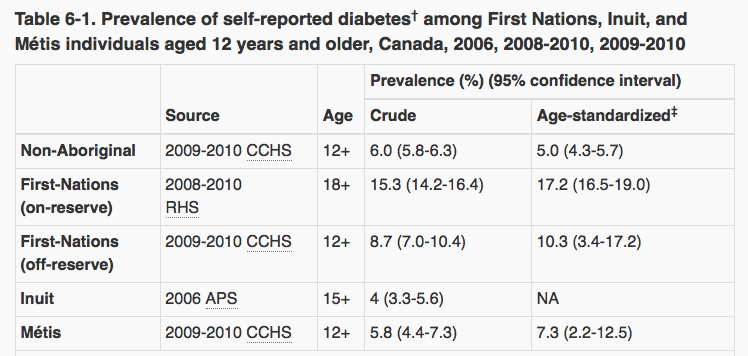

Aboriginal people are three to four times more likely to develop type-2 diabetes than the rest of the Canadian population (‘Diabetes in Canada’, 2011). Type-2 diabetes occurs when the pancreas in the body develops a partial resistance to insulin (‘Diabetes in Canada’, 2011). Insulin helps convert food to energy or sugar (glucose), although when the body cannot properly use the insulin, blood sugar rises and this can lead to serious complications which include damage to the heart, kidneys, eyes and nerves (‘Diabetes in Canada’, 2011).

The Determinants of Health

The many factors that combined together, affect the health of individuals and communities are known as the determinants of health. The determinants of health include income and social status, level of education, the physical environment, culture and traditions, employment, personal behaviours, social support networks, genetics, access to health services and much more (‘Determinants of health’, n.d.). The context of people’s lives determines their health, therefore individuals' are unlikely to be able to directly control many of the determinants of health (‘Determinants of health’, n.d.). The following video explains how the determinants of health affect individuals’ and populations health.

source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nTqknri15fQ

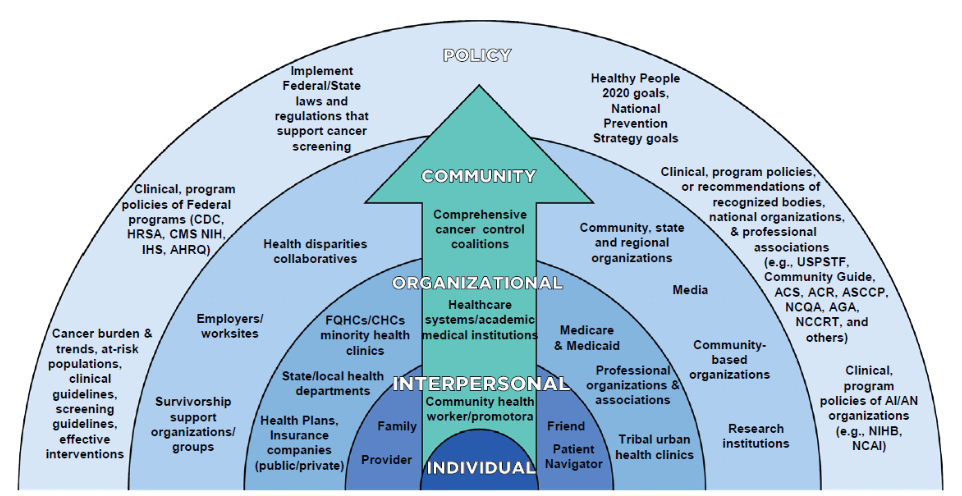

The Social Ecological Model (SEM)

The Social Ecological Model (SEM) is a framework used for understanding the multiple levels of a social system and interactions between individuals and the environment within the system (UNICEF, 2017). There are five hierarchal levels of the SEM, of which include the individual, interpersonal, community, organizational, and policy level (‘Social ecological model’, 2015). Information about each level within the SEM can be found here: SEM

Using the SEM enables us to closely examine and analyze interrelationships between an individual's personal dimensions with the multiple components of their life context and how each level within the SEM can have a significant impact on the development of type-2 diabetes among Aboriginal people.

Policy Level

The Indian Act – Healthcare. Under the Act, the government manages Indian lands, resources and moneys (Henderson, n.d). The Indian Act also defines eligibility for Indian status, where status-Indians have certain privileges, such as the right to not pay taxes on certain goods and live on-reserve lands, whereas non-status Indians do not (Henderson, n.d). As a result, this has created discrimination against non-status Indians who are often marginalized by their own people due to their place of residence (MacDonald & Steenbeek, 2015). Furthermore, non-status Indians must access programs and services designed for the general Canadian population, which include services that are not culturally sensitive thus may not meet their specific health needs (MacDonald & Steenbeek, 2015).

The Indian Act – Culture & Tradition. The impact of colonization, the banning of cultural practices, and the promotion of assimilation policies has resulted in the loss of traditional Aboriginal culture and has created a physical and financial dependency on provincial resources (MacDonald & Steenbeek, 2015). Aboriginal tradition includes hunting, fishing and harvesting, but with restrictions on the land and on rights, Aboriginal people can no longer engage in these traditional activities. This issue, how it affects health and the development of type-2 diabetes will be discussed later on in this post. A documentary about Aboriginal colonization can be found here: Canada's Dark Secret.

Non-Insured Health Benefits Program (NIHB). This plan includes services such as dental care and eye care, drugs and pharmacy products, medical transportation and much more. Non-status Indians (not registered as Indians under Indian Act) cannot benefit from this program, further marginalizing this vulnerable population. Without assistance from this program, Aboriginal people may not be able to afford the medication needed to manage their diabetes and may not have access to transportation to visit health clinics to prevent and manage diabetes. Information about eligibility and the program can be found here: NIHB

Community Level

A lack of trust and confidence in the Canadian government still prevails among the Aboriginal population, which often leads to delayed efforts and unproductive cooperation (Leung, 2016).

Media. Media images greatly influence individuals’ perceptions and understanding of the world and can contribute to the formation of one’s identity and perceived place in society (Knopf, 2010). In mainstream media discourse concerned with Aboriginal people, stereotypes and prejudice are often portrayed, which can lead non-aboriginal and aboriginal to develop false notions about Aboriginal people (Knopf, 2010). This further perpetuates discrimination within and without the community, and acts as a barrier to interacting with non-Aboriginal people and seeking care for their health (Cameron et al., 2014).

Organizational Level

Access to healthcare. Aboriginal people face more challenges than the non-aboriginal population in maintaining an acceptable level of health. Aboriginal people perceive access to health services to be very difficult and limited (Cameron et al., 2014). Under the Health Care Act, access is defined as an equitable distribution of services to those in need (Cameron et al., 2014). Also, according to the WHO, access and use of services that prevent and treat disease greatly influence health (‘Determinants of health’, n.d.).

24% of Aboriginal people rate the care they receive as worse than that of Canadians (lack of quality care and accessibility as main reasons) (Cameron et al., 2014).

15% of Aboriginal people reported unfair or inappropriate treatment from healthcare workers (Cameron et al., 2014).

“I want someone to be there as a translator because sometimes we don’t understand high words in English when we are questioned” (Cameron et al., 2014, p.E9).

“Being Aboriginal I’m treated like I don’t count, so that’s one of the reasons why I don’t go (to the hospital) (Cameron et al., 2014, p. E11).

It is evident that factors such as education level, emotions, language and communication are significant barriers to accessing healthcare services. Aboriginal people are often confronted with issues related to culturally appropriate healthcare access and services in both rural and urban areas, and their fear of judgement by mainstream healthcare providers affects their decision to seek healthcare services for their health needs (Health Canada, 2012; MacDonald & Steenbeek, 2015).

Environment. In rural areas, such as on-reserve lands, access to care may be restricted due to lack of transportation, lack of home support, limited access to healthcare providers and a lack of economic support for accessing certain healthcare services (MacDonald & Steenbeek, 2015). Furthermore, there is a frequent turnover of healthcare professionals in remote areas of Canada, which greatly affects medical management, ranges of services offered and access to healthcare services (MacDonald & Steenbeek, 2015). As a result, Aboriginal people disengage in healthcare services, further worsening existing illnesses such as type-2 diabetes (MacDonald & Steenbeek, 2015).

Interpersonal Level

Customs & Traditions. The influence of non‐Aboriginal Canadian living has a profound impact on the Aboriginal population in terms of diet, physical activities, and other social habits (Leung, 2016). According to the WHO, customs and traditions, as well all support from families, friends and communities is linked to better health (‘Determinants of health’, n.d.).

One Aboriginal elder stated, “Our communities have become disrupted… We don’t have water to go fishing, to go hunting and gathering. All of that has been taken away and we’re like a jail here" (Oster et al., 2014, p.7). As mentioned previously, traditions have changed due to colonization practices from the past. Laws and regulations determining resource and land allocations, and Aboriginal have had a direct effect on Aboriginal cultures, traditions and health (Webster et al., 2017). The introduction of European food and sedentary lifestyles are risk factors that are highly associated with type-2 diabetes development.

Individual Level

Genetic. According to the WHO, inheritance plays a part in determining healthiness and the likelihood of developing certain illnesses (‘Determinants of health’, n.d.). The thrifty gene effect is a theory which proposes that Aboriginal people are predisposed to conserve calories due to a specific gene that has developed through evolution in order to help them easily store fat during periods of food abundance in order to provide energy through periods of starvation (Leung, 2016). If the theory is correct, the simple fact of being Aboriginal would predispose individuals’ to being overweight or obese, which can subsequently contribute to the development of type-2 diabetes.

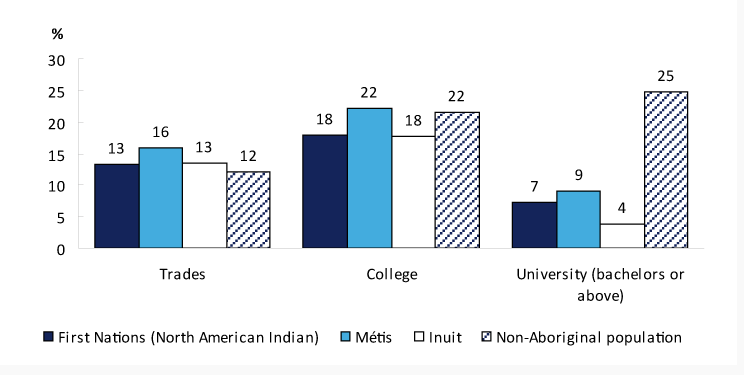

Level of education. According to the WHO, low education levels are linked to poor health (‘Determinants of health’, n.d.). A low level of education can be a significant barrier to understanding diabetes prevention, management and treatment measures. An Aboriginal man from Webster et al.,’s (2017) study stated, “It’s hard because I can’t read or write so I need a person who can explain it to me” (p.29). It is clear to see how education is linked to poorer health because illiteracy reduces one's ability to be informed about diabetes prevention, management, available treatments, current research available and so on.

Income. According to the WHO, income is directly linked to health, thus the greater the gap between rich and poor, the greater the difference in health (‘Determinants of health’, n.d.).

The median total income for Aboriginal people aged 25-54 in 2005 was approximately

22,000$, whereas the rest of the Canadian population averaged an income of approximately 33,000$ (‘Median Income’, 2015).

One Aboriginal woman stated, “When you’re diabetic, you have to try and take what you can to keep you alive … I can’t afford 30$ for a bottle of pills because I’m on a fixed income…so there’s nothing I can do” (Senese & Wilson, 2013, p. 224).

Less income translates to less money to buy healthy food, to pay for health treatments that are not covered by healthcare insurance and to attend school. Furthermore, if they are non-status Indians, they are not covered by the NIHB program which could greatly improve access to healthcare through its medication and transportation coverage.

Food insecurity. Food insecurity exists when the availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or the ability to acquire such food in socially acceptable ways is limited or uncertain (Willows et al., 2011). In a study conducted by Willows et al., (2011), researchers found that 29% of Aboriginal adults living off-reserve across Canada live in food-insecure households. These rates are approximately three times higher than then rest of the Canadian population (Willows et al., 2011).

Locally harvested or traditional food in Aboriginal communities were usually rich in protein and essential micronutrients, however today, the supply of traditional food for Aboriginal people is often inadequate due to land and hunting restrictions (Leung, 2016).

We can deduce that the reason why Aboriginal people often resort to processed food, which is often poor in nutritional value, is due to the high levels of food insecurity across the Aboriginal population, restrictions placed by the government on land and hunting, along with the many other factors that lead to food insecurity such as employment, income and level of education (‘Treaties’, 2010).

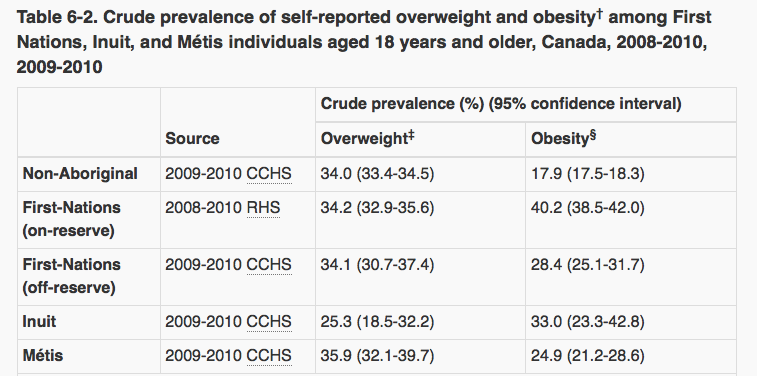

Lifestyle – Weight. As their lifestyle transition away from the physically demanding hunter‐gatherer‐harvester, modern day Aboriginals are more sedentary and reliant on motorized transport (Leung, 2016). This drastically reduces their daily level of activity and caloric expenditure which are risk factors for weight gain and the development of type-2 diabetes.

The table below presents crude prevalence of self-reported overweight and obesity among Aboriginal people aged 18 years and older, in Canada, from the years 2008 to 2010.

Knowledge & Beliefs. Several factors influence Aboriginal people’s knowledge and beliefs in regards to health. According to the WHO, personal behaviour and how individuals deal with stresses and challenges in life greatly affect health (‘Determinants of health’, n.d.).

European colonization and traditions have changed the lifestyles and traditions of Aboriginal people, rendering them less healthy and active than their ancestors (Webster et al., 2017). One participant stated, “Nearly every processed food is sugar, sugar, sugar…the only sugar we used to have was wild sugar (Webster et al., 2017, p. 28). Colonization continues to have a direct effect on Aboriginal health, including reduced access to traditional medicines and foods (Webster et al., 2017).

Many participants from the study also said they have little or no trust in a system that tells Aboriginal people how to live their lives (Webster et al., 2017). One participant stated, “They’re white people who run the diabetic programs and come up with all these things to do for natives with diabetes”, whereas another mentioned, “I feel like it’s all scare tactics and they’re just trying to shame me and I feel real bad about myself… I prefer not to go because I don’t want to feel that way” (Webster et al., 2017, p.29). Through these quotes we can deduce the lack of trust Aboriginal people have in the government and health system can lead them to avoid seeking medical help.

Conclusion

In Canada, Aboriginal people are a vulnerable population given that they have a higher prevalence of inequalities than the rest of the Canadian population. Health inequalities are very closely linked to the determinants of health, as we have seen throughout this post. People from vulnerable groups such as the Aboriginal people of Canada, are more likely to suffer from illness, die younger and not benefit from optimal access to healthcare services (Cameron et al., 2014). As we have seen through the application of the SEM and determinants of health to analyze the development of type-2 diabetes in the Aboriginal population, it is clear that they face more challenges in maintaining an acceptable level of health that the non-aboriginal population. Research has documented the above trends, although not much has been done to change them (Cameron et al., 2014). Stakeholders at every level must reinvest in social justice to decrease health inequalities for vulnerable populations, to promote equality and restructure social relationships in society (Cameron et al., 2014).

References:

Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative. (2013, September 13). Retrieved March 5, 2018, from

https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/first-nations-inuit-health/diseases-

health-conditions/diabetes.html

Cameron, B. L., Plazas, M. D., Salas, A. S., Bearskin, R. L., & Hungler, K. (2014). Understanding

inequalities in access to health care services for Aboriginal people. Advances in

Nursing Science, 37(3), E1-E16. https://doi:10.1097/ans.0000000000000039

The determinants of health. (n.d.). Retrieved March 6, 2018, from

http://www.who.int/hia/evidence/doh/en/

Diabetes in Canada: Facts and figures from a public health perspective – First Nations, Inuit,

and Métis. (2011, December 15). Retrieved March 6, 2018, from

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/chronic-diseases/reports-

publications/diabetes/diabetes-canada-facts-figures-a-public-health-

perspective/chapter-6.html

Employment. (2015, November 30). Retrieved March 05, 2018, from

https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-645-x/2010001/employment-emploi-eng.htm

Health Canada. (2012, March 27). Eating habits and nutrient intake of Aboriginal adults aged

19-50, living off-reserve in Ontario and the western provinces. Retrieved February 26,

Henderson, W. B. (n.d.). Indian Act. Retrieved March 04, 2018, from

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/indian-act/

Knopf, K. (2010). "Sharing our stories with all Canadians": Decolonizing Aboriginal media and

Aboriginal media politics in Canada. American Indian Culture and Research Journal,

34(1), 89-120. https://doi:10.17953/aicr.34.1.48752q2m62u18tx2

Leung, L. (2016). Diabetes mellitus and the Aboriginal diabetic initiative in Canada: An update

review. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 5(2), 259.

https://doi:10.4103/2249-4863.192362

Macdonald, C., & Steenbeek, A. (2015). The impact of colonization and western assimilation on

health and wellbeing of Canadian Aboriginal people. International Journal of Regional

and Local History, 10(1), 32-46. https://doi:10.1179/2051453015z.00000000023

Median total income in 2005 by Aboriginal identity, population aged 25 to 54. (2015,

November 30). Retrieved March 05, 2018, from https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-645-

Oster, R. T., Grier, A., Lightning, R., Mayan, M. J., & Toth, E. L. (2014). Cultural continuity,

traditional Indigenous language, and diabetes in Alberta First Nations: a mixed

methods study. International Journal for Equity in Health, 13(1), 1-11.

https://doi:10.1186/s12939-014-0092-4

Postsecondary educational attainment by Aboriginal identity, population aged 25 to 54, 2006.

(2015, November 30). Retrieved March 6, 2018, from https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-

Treaties with Aboriginal people in Canada. (2010, September 15). Retrieved March 08, 2018,

from https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100032291/1100100032292

UNICEF. (2017). Programme Evaluation of UNICEF Bangladesh Communication for

Development (C4D) Programme from 2012 to 2016. Retrieved February 26, 2018, from

Social ecological model - SEM. (2015, October 27). Retrieved February 22, 2018, from

Webster, E., Johnson, C., Kemp, B., Smith, V., Johnson, M., & Townsend, B. (2016). Theory that

explains an Aboriginal perspective of learning to understand and manage diabetes. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 41(1), 27-31. https://doi:10.1111/1753-

6405.12605

Willows, N. D., Hanley, A. J., & Delormier, T. (2012). A socioecological framework to

understand weight-related issues in Aboriginal children in Canada. Applied

Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 37(1), 1-13. https://doi:10.1139/h11-128

Willows, N., Veugelers, P., Raine, K., & Kuhle, S. (2011). Associations between household food

insecurity and health outcomes in the Aboriginal population. Health Reports -

Statistics Canada, 22(2), 1-6.

I came from a Pacific Island nation called Papua New Guinea. My country shares borders with Indonesia, Australia and Solomon Islands..I usual search on Youtube any interesting documentaries. Whilst looking up youtube videos I came across a documentary on people who suffer diabetes and there are real treatment from multivitamincare org. My wife diabetes symptom was diabetic neuropathy. We didn't know she was diabetic until we went to my doctor complaining about constant foot pain. After a multitude of tests for everything from rheumatoid arthritis to muscular dystrophy, an emergency room physician checked her blood sugar.After reviewing a letter written by my doctor, where I read he had prescribed Celebrex for her due to pain of Arthritis which had really…